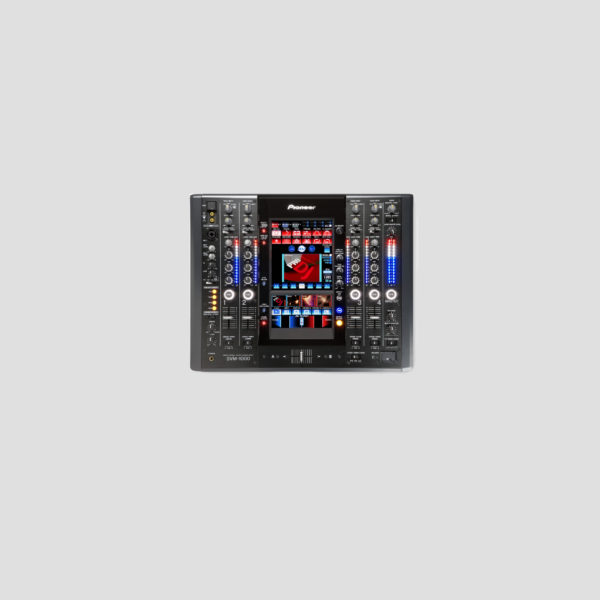

My big retro mix lasted for about two hours and honestly, I was terrible. It might have partly been my mood that day, but it felt like the now unfamiliar demands of the equipment made it difficult to get into a groove. My movements were too heavy handed. I kept overcompensating with the pitch control. There was no fall-back option of using the BPM readouts to at least establish a decent run of mixes. It also made me think about how important context is when we DJ. The old music wasn’t really resonating with me, but I know it could have been different playing with some good friends.

Despite my poor performance the mix had the intended effect: leaving me with plenty to think about.

For instance, while stuffing a USB stick full of music is possible, it might not always be preferable. Reconnecting with CDs made me think that they were actually a decent middle ground between vinyl and modern digital formats. To stress, I’m not cheerleading a CD revival, but there’s maybe something to be said for carrying fewer tracks of a higher quality. People often talk about the benefits of knowing your music more intimately. If you place any stock in this idea, the size of our digital collections and the way we catalogue them might be worth reflecting on.

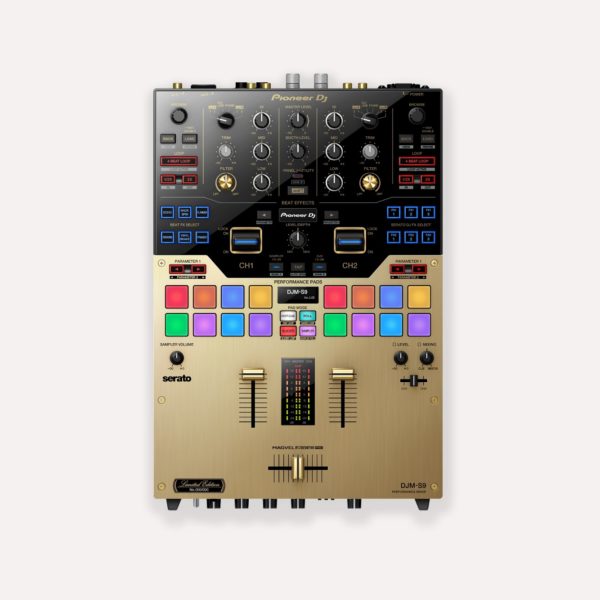

When we step back from the functionality we now have, notice how plenty of it makes us think about music as parts. Loops, hot cues, sampling and other performance tools are incredible for combining pieces of a track to make something unique. Many DJs flourish using these tools. But even as the technology has moved in this direction, others might find that music treated this way isn’t natural to them. I probably wouldn’t have even noticed this without stepping back in time, so to speak.

Meanwhile, the net effect of having such effective tools to help us mix must be that DJ sets feature fewer “mistakes” these days. How people feel about this will probably vary, from indifference in newer DJs to frustration in some older ones. I’ve argued in the past that DJing shouldn’t be easy, but my view has now softened. DJing means so many different things to so many different people that it no longer feels relevant to argue for it having some kind of fixed essence. Some DJs and crowds prefer traditional setups of two decks and a mixer and might welcome the odd mistake; others will be accustomed to flawless combinations of sounds delivered with the assistance of technology. There’s no reason multiple schools of thought can’t coexist.

We should also momentarily celebrate just how good new DJs now have it. When I wanted to learn to mix in the late ‘90s, I wound up mail ordering what turned out to be a photocopied pamphlet that contained incomprehensible diagrams and cost almost £20. (It was funny to discover, after buying the faulty CDJs, that I’m still prone to being scammed.) The access to information and affordable DJ setups these days, especially if we include apps and software, means that many, many more people are getting involved and they have loads more ways to express themselves.

What will DJs 20 years from now think about our current technology? Will it seem antiquated in the same way as this gear from the early 2000s? I’ll have to get back to you on that one.