The market for DJ gear gets going

As we said earlier, there was pretty much no equipment on the market built specifically for DJs at the start of the ‘70s. DJs relied on mono mixers designed for radio broadcasting, while turntables came from the hi-fi market. The nature of the game was making do. But by the end of the ‘70s the situation had improved drastically.

The Technics SL-1200 was released in 1972, and although it was originally positioned as a high-end consumer product, DJs quickly sensed its potential. Like the SP-10 before it, the SL-1200 had a direct-drive motor, with the platter mounted directly onto the deck’s motor, rather than via a belt. This greatly improved torque meant that DJs could cue, back-spin, and nudge the platter in ways that were often impossible with older belt-driven models. The DJ could also adjust the pitch by +/- 8% via two small rotary controls, while the deck’s quartz lock reduced the playback drift that a lot of older turntables were prone to.

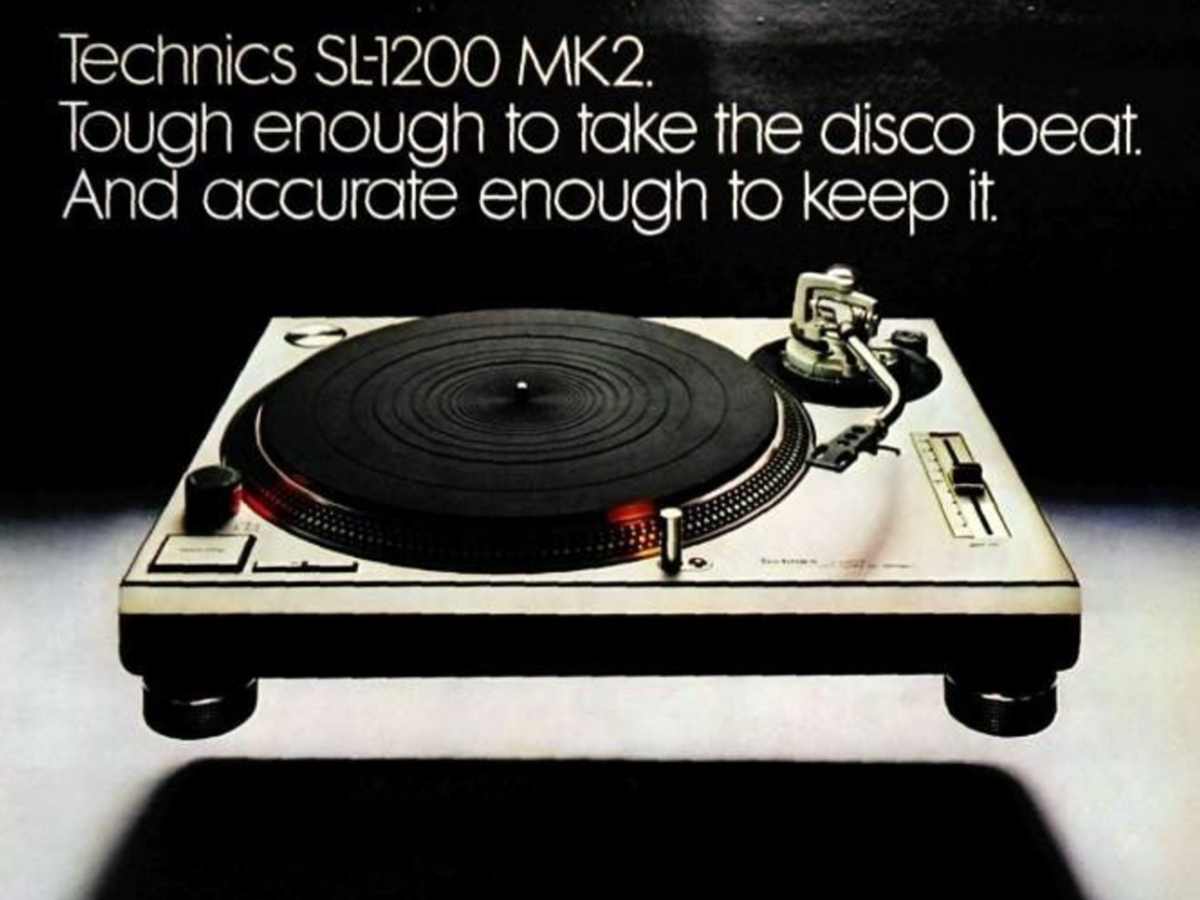

The SL-1200 may not have been designed with DJs in mind, but its successor, 1979’s SL-1200 MK2, certainly was. The MK2 featured the now iconic +/- 8% pitch slider, improved quartz lock, better torque, anti-skip feet, and a heavier chassis, which reduced vibration and feedback. In fact, the MK2s were so durable that many of the units from back then are still in use today. Its design, meanwhile, became the industry standard for DJ decks, a fact that remains to this day.

“The invention of the Technics was groundbreaking,” said Bill Brewster. “It completely changed the game. And if you look at how quickly the nightclub industry moved over to them, it was swift.”

A year before the release of the SL-1200, the market for DJ mixers got started. The Bozak CMA-10-2DL, released in 1971, was the first widely available DJ mixer. It featured four stereo inputs, a cueing system, EQ, and a wide, rack-mountable design. It was the first time that DJs had a mixer tailored specifically to their needs. The Bozak, which maintains a reputation for quality audio to this day, wound up in the booths of the most influential clubs of the era—The Gallery, Studio 54, The Paradise Garage.

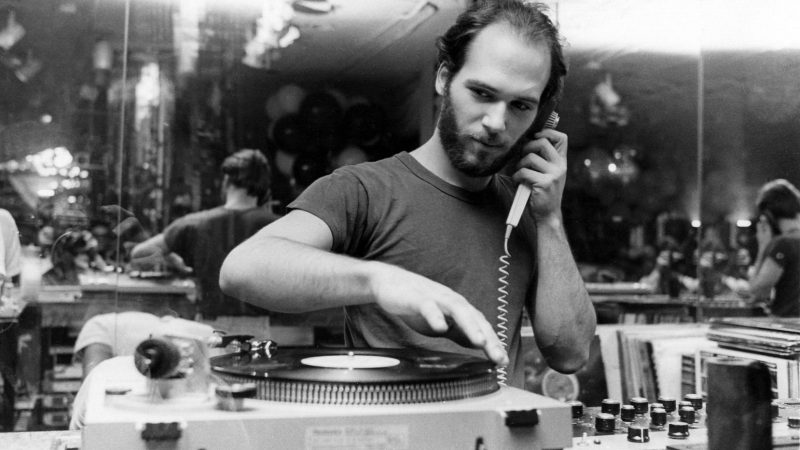

“There was one store in New York called AST and it was a major store for lights and sound,” recalled Morales. “On the wall they had all the rotary mixers. I’d go there with no money, but I’d still go after work just to listen and look. Some of those mixers, like the Bozak and others, weren’t anywhere near my price range, but it didn’t matter. I liked just being there, seeing the gear.”

The CMA-10-2DL was designed by Louis Bozak in collaboration with the engineer Alex Rosner, a major behind-the-scenes figure who is known as the inventor of the DJ mixer and the sound designer of Mancuso’s Loft. Rosner had designed a basic mixer with a cueing system for Francis Grasso called Rosie, which fed into the design of the CMA-10-2DL.

Cheaper mixers with crossfaders arrived at the back end of the ‘70s. In the UK there was the Citronic SMP101 (about which very little information can still be found) while the US equivalent was the GLI PMX 7000. Released in 1977, a product advert for the PMX 7000 talked up its affordable price point of $299. (For context this is today the equivalent of around $1,600.) With vertical faders and a crossfader positioned below, the PMX 7000 would prove to be highly influential for the design of later DJ mixers.

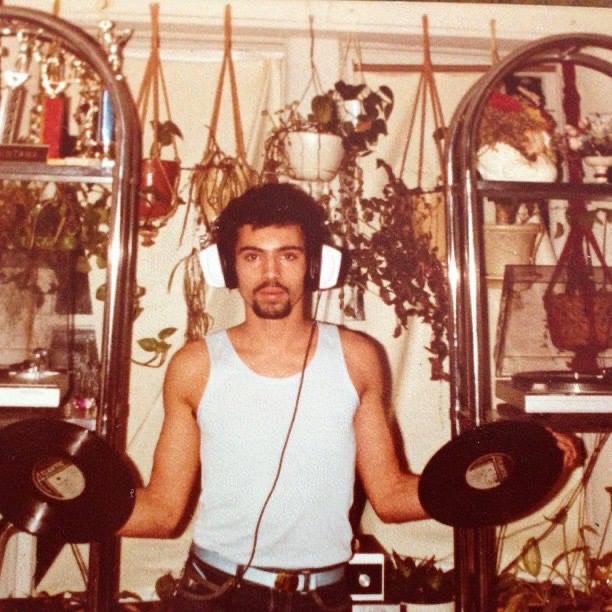

“We didn’t have crossfaders that went from left to right,” said Theodore. “Our crossfaders were up and down. And at one time we didn’t even have earphones.

“And then all of a sudden these companies started making mixers that actually had the earphone jack. So the equipment that we were buying was starting to change. The turntables were starting to change. They used to be belt drive, but then they became direct drive. Our mixers were really small, but then our mixes started to get bigger and bigger because they were putting on equalizers. So there were a lot of things that these electronic companies were doing to cater to the DJ.”

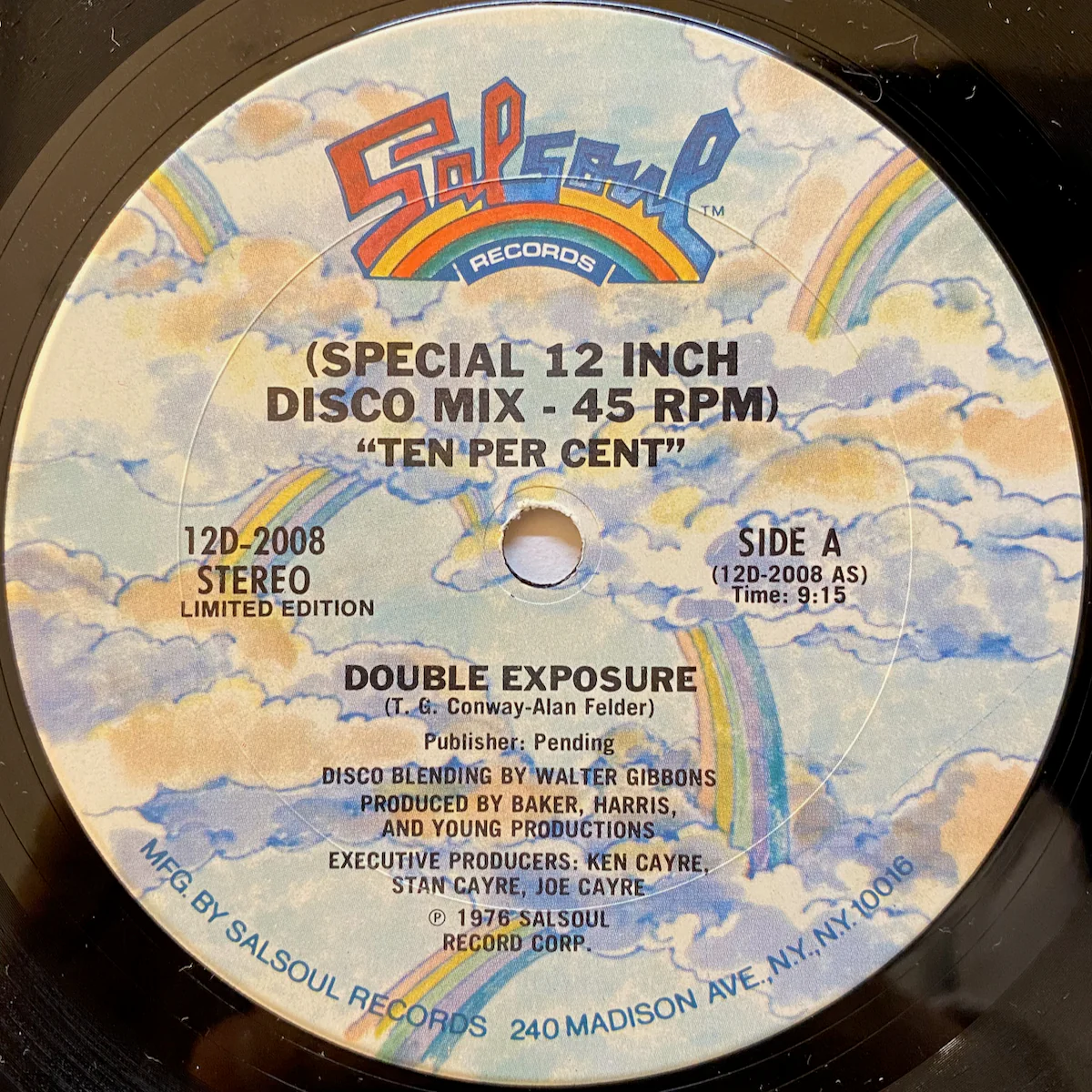

Although the format was only really used in leading New York venues, it’s worth mentioning the impact of reel-to-reel tape machines. The disco mixes that came to prominence in the ‘70s were often created in the studio by splicing tape and looping sections to make a track’s arrangement more DJ-friendly. These often exclusive versions were then passed to DJs and played back using the club’s tape machine.

“In New York they were technically advanced,” said Brewster. “Remixing and editing started there, and they were using reel-to-reel machines they brought in from the studio—quarter-inch tape. Later on, they used cassette tapes too. You could get cassette decks with variable speed, so you could actually mix using quarter-inch tape or cassettes as well.”

The ‘70s was also a foundational decade for the development of DJ-orientated soundsystems. Design for the Bozak mixer was also shaped by Richard Long, the now legendary sound engineer who designed systems for the Paradise Garage, Better Days, and Studio 54. Long’s builds for these venues shaped the platonic ideal of the club sound that we still hold now. His systems were known for deep, physical bass, warm mids, clear, detailed highs, dispersed sound, and plenty of oomph.