Back in 2010, an age when smartphones were still a fancy indulgence, YouTube only allowed ten-minute clips, and podcasting was just beginning to flourish, Pioneer DJ semi-accidentally caught the beginning of a wave, one that was about to engulf DJ culture.

“We filmed a radio show,” said Dan Tait from AlphaTheta / Pioneer DJ. “The show was on Ibiza Sonica Radio. Filming DJs playing in a studio just wasn’t a thing, many were bemused as to why we would want to film someone playing other people’s music, so we said, ‘Come on the radio, promote your night on the island… Oh, and by the way, there will be cameras.’” The stream was called the DJsounds Show, and it ran from 2010 to 2020, filming from locations around Ibiza, Berlin, Paris, and a studio in London.

As we know now, DJ streams would soon become massive. Boiler Room led the charge. Beatport Live, DJ Mag and Mixmag got in on the fun, shooting streams in their offices and at live events. And with channels like HÖR, Cercle, and My Analog Journal, by the end of the decade a new school had arrived.

The DJsounds Show stopped programming when COVID hit in 2020. “We didn’t want to compete with charitable streams, with artist streams,” said Tait. “So we figured we’d take a break.” Now, as the show relaunches, the DJsounds Show enters into a pretty different landscape.

“The streaming world has really matured over the last 15 years,” Tait said. “We want our new show to reflect that.”

“Matured” may be putting it lightly. From 2010 to 2020, evolutions in technology and culture made DJ streams a cornerstone of dance music. When the pandemic hit in 2020, they became even more important. In the absence of IRL events, streams were an essential point of contact between DJs and their fans.

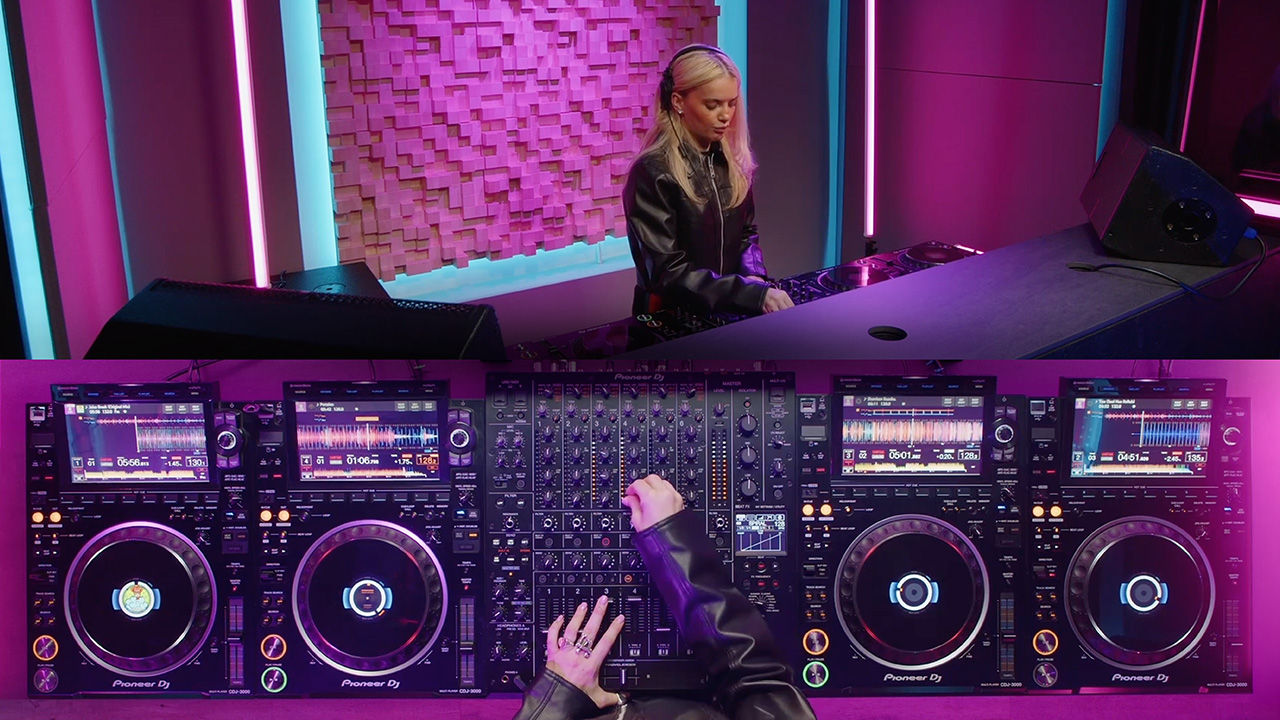

Back in the early 2010s, even the big streams had a scrappy DIY charm, typically showing live footage of a private party from a single, unchanging angle. Today, they tend to be high-production and high-stakes. Dozens of people can work on each video, filming from multiple angles, and doing post-production work to get the sound and visuals just right.

The videos are even promoted the way you would a record—or, perhaps more fittingly, a mix CD, that once-essential format that’s more or less been reincarnated as the DJ stream. Almost all DJ streams are recorded, then edited and published at a later date. In other words, they are, for the most part, no longer live streams.

What they are is a professionally produced digital asset with a broad reach and a long shelf-life, potentially racking up millions of views over years, and occasionally launching the career of a DJ in one fell swoop. Even without that kind of stellar result, they can be incredibly valuable to electronic performers, easily trumping records when it comes to showing off what they do best.

Artists plan their sets for months. They treat them more like a recorded studio mix than a live stream. In turn, Boiler Room treats the stream as an official release, complete with a marketing campaign and a carefully planned roll-out. The end result can be incredibly beneficial, both to Boiler Room and the DJ playing. Both parties have learned to treat it that way.