Recording best practice

Now you have your setup in place, it’s time to start ripping. Well—not quite yet.

First you should clean your record to prevent unwanted noise making it onto your recording. If you’ve DJ’d with the record in the past it might be especially dirty, so don’t skip this stage. Specialist tools—cleaning fluid, a record brush, an anti-static cloth—are your friends. There are also fancy record-cleaning machines (like a car wash for your 12-inches), but these may not be worth it unless you’re a ripping obsessive.

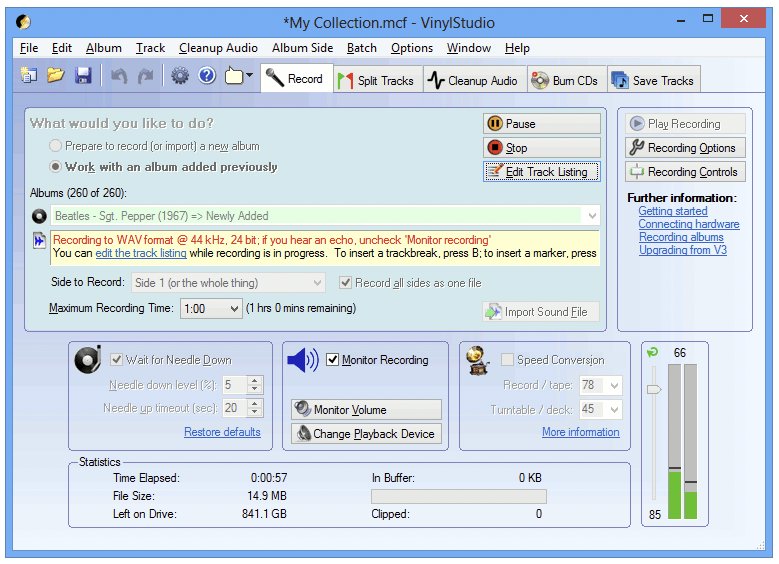

Next, set your input level. Adjust the volume of your audio interface so that the meter in your recording software is showing a strong signal that’s well below the maximum. (In most software, the input level will show green, then yellow as volume increases, then hit red when it’s too loud. Stick with yellow at most.) Check the loudest part of the record to be sure the input isn’t clipping. If in doubt, err on the quiet side. It’s easy to boost the level of a rip later. A distorted recording is much harder to clean up.

Now, finally, hit record in your software and drop the needle on the record. Silences at the start or end of the recording are fine, you can tidy these up later. While recording, try not to stomp around the room or touch the surface your turntable is on. These sounds can be picked up by the stylus, causing troublesome booms and rumbles in your rip. Additionally, keep the volume down of the track you are ripping as speakers can produce unwanted vibration, which may negatively affect your recording.

Editing the recording

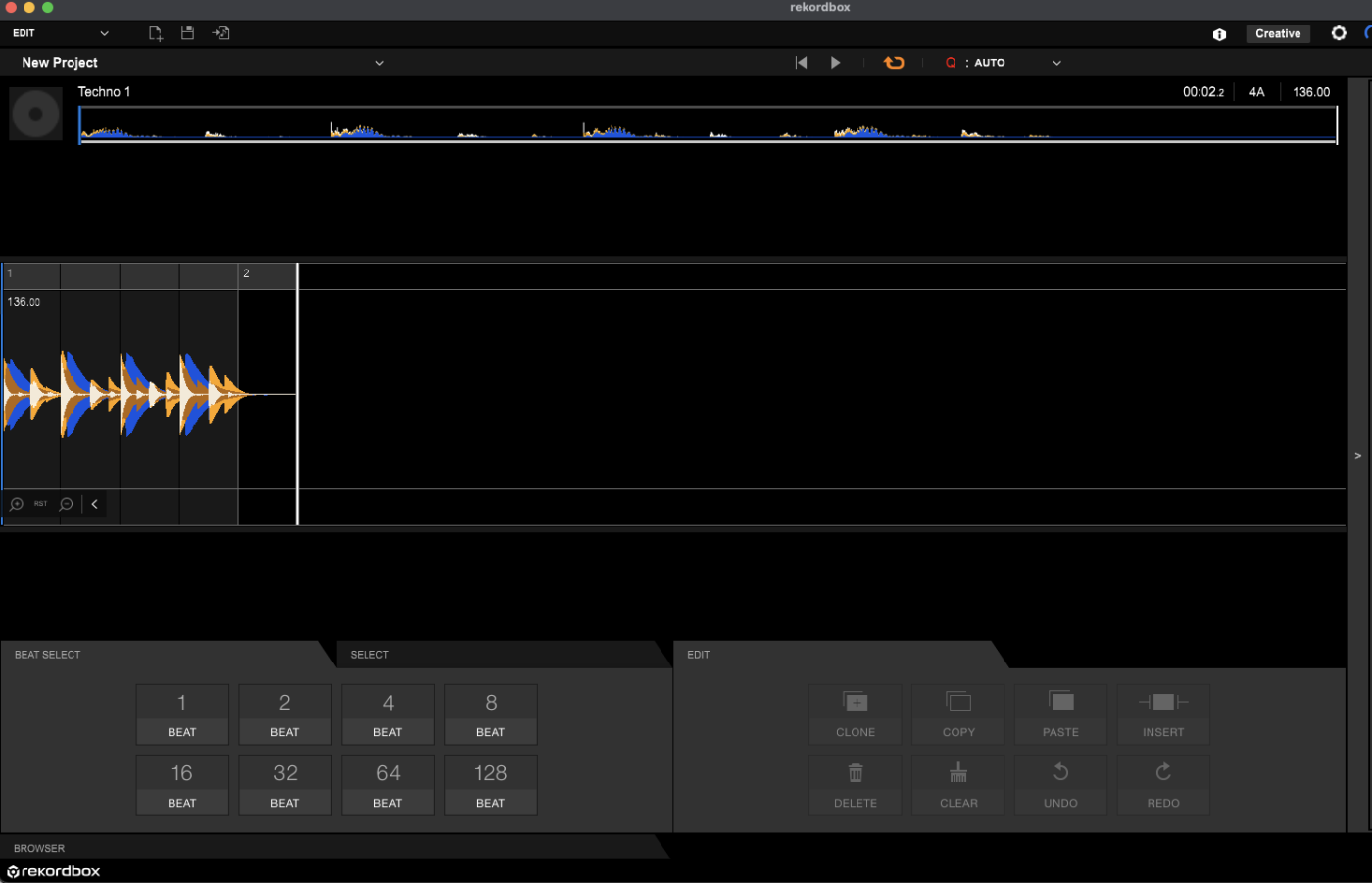

Now you’ve got a recording, the fun can begin. A few technical steps will transform the raw audio into a polished, useful rip. Start by deleting silence at the beginning and end of your file. In most software you can do this by highlighting the unwanted areas and hitting “delete” or similar. Specialized vinyl ripping software might automatically do this for you.

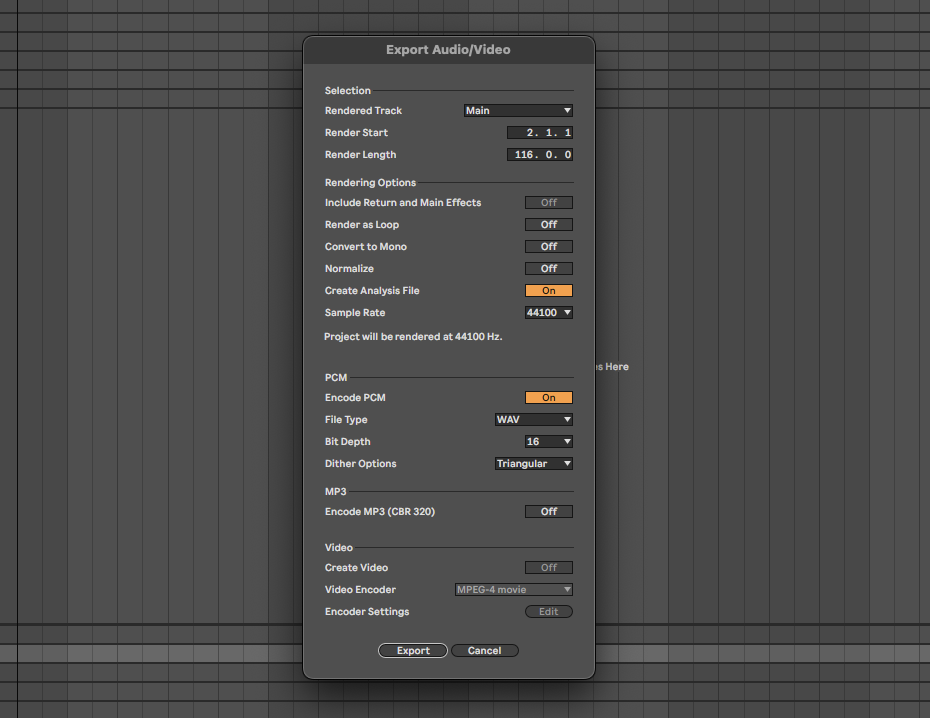

Next, you need to clean up the audio. Vinyl is a noisy medium, and your records—especially older, well-loved ones—are likely to feature unwanted sounds. A little bit of noise is fine, but loud hiss or a deafening click might make your rip difficult to DJ with. Fortunately, there are tools that address this. But note that, if you can, it’s always easier to get rid of clicks and noise by thoroughly cleaning your record first, rather than using fancy tricks later.

It’s particularly important to get rid of sharp clicks in your recording, as these will make it harder to get the rip loud in the next step. Audacity has a tool to replace clicks, and specialized vinyl software will offer automated features to address both clicks and surface noise. If you’re using a production DAW, you might need to get an additional audio repair VST, like iZotope’s RX.

Whatever you use, be careful not to overdo it. When slapped on too hard, automated cleanup algorithms can make a rip sound lifeless and digital. They might work better on some kinds of music than others. If you’re not sure whether you’re making things better or worse, it’s safer to leave a bit of noise in.