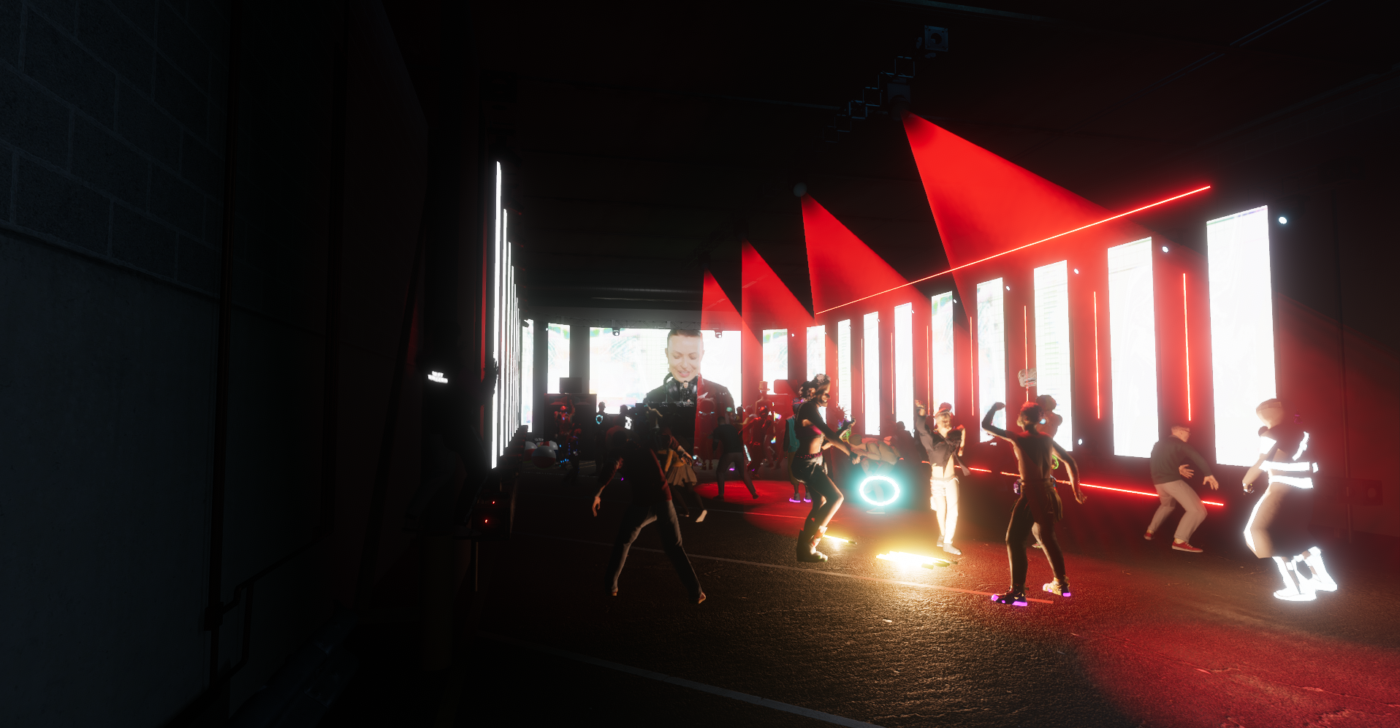

While virtual promoters are keen to embrace many unique possibilities of digital space, most still seem reluctant to experiment with fantastical environments. Instead, they create digital approximations of clubs with low ceilings, laser lights, decks and speaker stacks. Given that one could fashion literally any kind of space from pixels, why are these clubs so aesthetically traditional?

VRChat clubbing veteran Greene thinks it’s because that’s simply what the audience wants. “It’s not that they can’t imagine more, because people create those worlds, and nobody uses them,” he said. “It’s a strange phenomenon—people definitely gravitate away from fantastical, overdone stages.”

Club Matryoshka is unusual in this regard. A virtual event series that started life in the Philippines before the pandemic, their team take months to plan and organise each in-game world, with imaginative spaces inspired by brutalism, aliens, insects or the experimental American architect Lebbeus Woods. “We really embraced the infinite potential of URL,” said Wieneke.

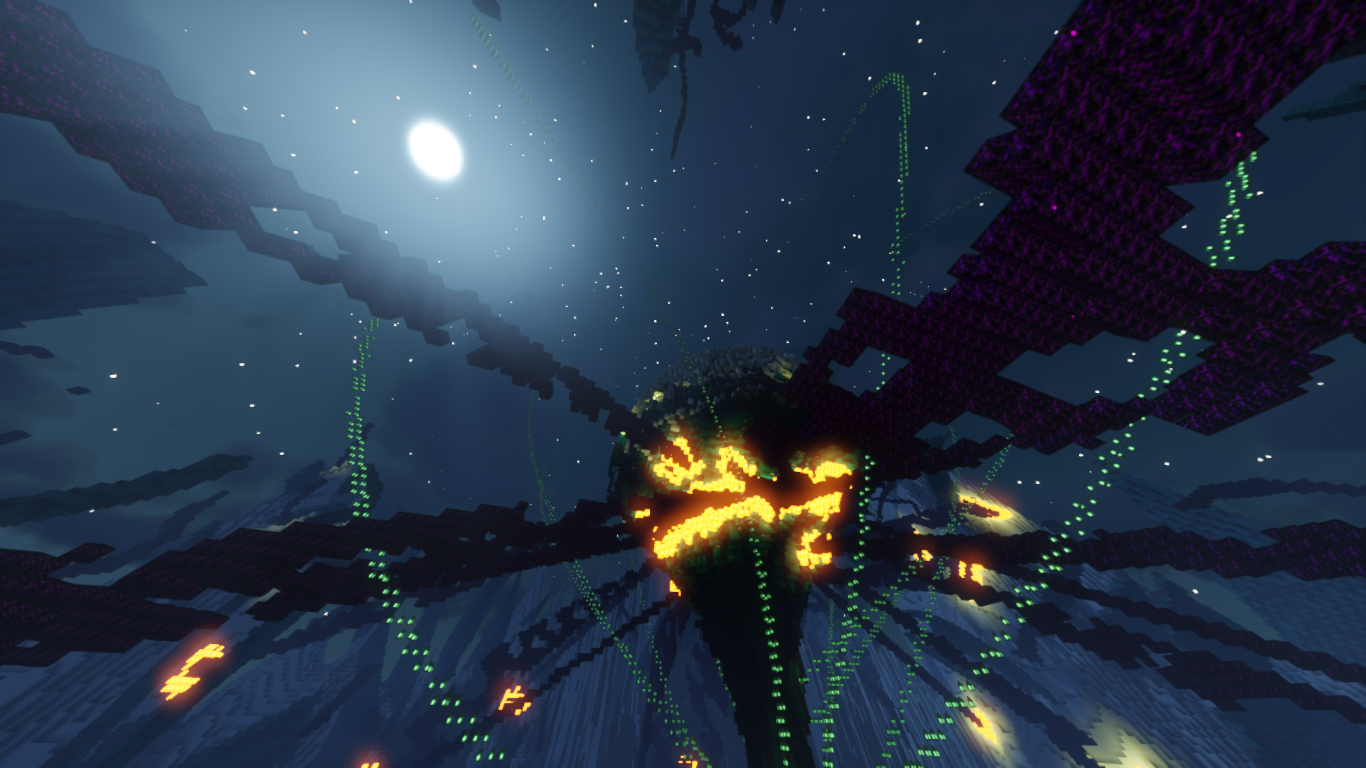

No matter how fantastical or realistic the vision, many non-gamers would find it hard to feel immersed in a space like Minecraft, with its blocky, low-resolution graphics. This issue speaks to an unresolved problem with virtual club spaces. Promoters have to make a trade-off between technological accessibility and the complexity of the experience. With basic tech you can draw in more attendees. Go for more sophisticated software and you will get better graphics and perhaps deeper immersion, but you might exclude the average punter who doesn’t have a gaming computer or VR headset. “We don’t expect everyone to have the liberty or the luxury of high-end machines that can handle more demanding software like VRChat. We decided to run our club on Minecraft because even a potato laptop can run it,” Wieneke said.

“That’s the big challenge of virtual clubs,” said Raynaud, “this compromise between technology and accessibility. We chose Minecraft because it’s one of the world’s most-played games, and so many people already have accounts. We wanted this to be as simple as walking into a real club.”

Over lockdown these teams built servers, communities and digital environments that will outlast the pandemic. They aren’t the same as a real club with real bodies, nor do they need to be. They have their own qualities, their own ways of encouraging people to share and interact with music. “There’s still people interested,” said Krauss. “These spaces aren’t going anywhere.”

As long as virtual parties are meaningful for digital ravers, they will have a continuing place in our cultural firmament. “VR parties and online shows make me feel like nothing is impossible,” said Wieneke. “If you feel lonely or out of place where you are, I learned it’s possible to find your people elsewhere. Virtual clubbing makes me feel less alone.”

Tips for aspiring digital promoters:

- Try building on an existing platform before creating your own.

- Metaverse platforms like Decentraland and Sandbox are eager for digital event content, while platforms like Minecraft are open for all. “Try being a promoter in a digital space owned by somebody else,” recommends Jack. “If you get traction from it, then you can go off and start something on your own.”

- Get involved in your chosen platform’s community before you make your own event.

- Become immersed in a scene to see what people have already built, so you can come up with a unique concept. “You need a selling point, rather than just being another space,” says Denman. His USP with Tube is being the first space for underground UK music in VRChat.

- Keep on top of the tech.

- “Get help for the technical side or make sure you have sufficient knowledge and experience,” says Krauss. “The technology isn’t quite there yet to make virtual parties happen easily. You need to know your shit.” If you are struggling, you will often find helpful communities of programmers and makers on online forums like Reddit.

- Don’t forget to have fun.

- “Don’t think of it as a business,” says Raynaud. “The fun, music and gaming experiences should be the primary ideas that you always stick with. If you get to a point where you’re no longer enjoying it, maybe you’re going in the wrong direction.”