“There was also an idea to pack in as many different effects as possible, but we ultimately decided against that,” said Suzuki. “Rather than creating an overwhelmingly powerful effects unit, we chose to focus on a more fundamental question: what do DJs actually want to do when they use effects?

“The answer we arrived at was simple: wouldn’t it be amazing if DJs could improvise with track structures in real time and control the energy of the floor more freely? Creating breaks that weren’t originally there, or adding fills to push a moment further. That kind of freedom became the core concept.

“Our team at the time had many active DJs. We believed that DJing wasn’t just about the inherent power of the track itself, but about the feeling you get when you actively shape the music, almost as if you’ve suddenly become a genius, controlling the entire space. We wanted more people to experience that sense of freely commanding the energy of the floor, and we set out to build a piece of gear that could make that possible.”

However, this emphasis on controlling and building sound did introduce a big challenge. As Takagi pointed out, it’s easy to apply effects, but it’s surprisingly difficult to end them cleanly. “That challenge led directly to the creation of Release FX,” he said. “Even after layering multiple effects, DJs needed a way to return to the original sound instantly, with a single action. That was absolutely essential.”

There was also an unexpected but important piece of feedback the team received from a DJ: “You wouldn’t be able to use this in a club when you’re drunk.”

“That feedback was decisive,” said Suzuki. “From that point on, our goal became clear—we wanted RMX to be usable even in that state.”

Suzuki talked about the flexibility of the unit, especially through the use of the sub parameter controls. “Those sub-parameters change their labels depending on the selected effect, and preferences really vary from DJ to DJ, so we designed it to be highly customizable. When I saw James Zabiela switching those parameters and effectively playing the unit like an instrument, I remember thinking both ‘that’s a really interesting way to use it’ and being genuinely surprised.”

But in some DJ circles, the RMX-1000 became almost infamous for one feature in particular: its snare roll. “Looking at how people actually used the unit, I think a lot of DJs gravitated toward snare rolls,” said Takagi. “That made sense, because we were really asking a simple question: if someone wants to build excitement, what kind of sampler or effects unit would truly help them do that?

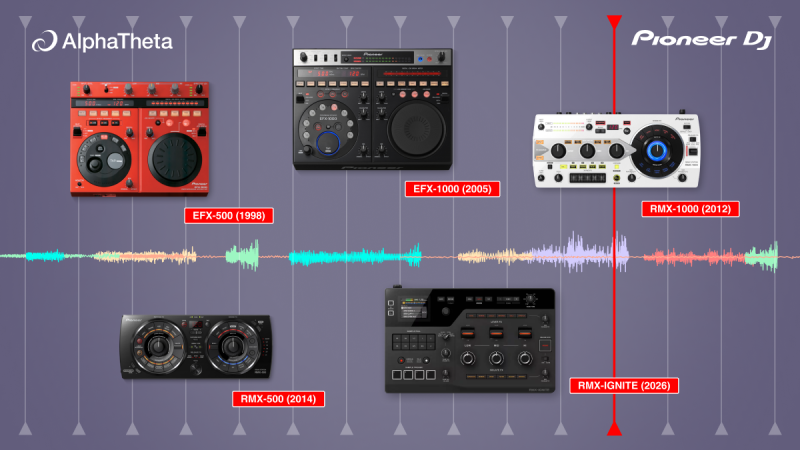

“At the same time, looking back, I think we may have been a little too influenced by the flashy trance scene of that era. The RMX-1000 sound became very recognizable—almost too recognizable—and over time, it risked becoming a sound people grew tired of.

“With the new RMX-IGNITE we took a different approach. We wanted to strip away that ‘obvious’ character and create an effects unit that DJs could use for a long time, without it feeling dated.”