Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa, Grandmaster Flash: The pioneers

“You got the b-boys that b-boy’d in the parks so they could release some energy. You have the graffiti artist that did drawings… to depict how they were feeling. Then you got the MCs that were writing down their feelings on paper. Then once the DJ played music they would get on the microphone and start spilling these words out so that they could get whatever’s bottled up inside them out. That’s basically how hip-hop was born.”

This is Grand Wizzard Theodore, widely credited as the inventor of the scratch, describing the creative atmosphere of The Bronx in the 1970s. Early in the decade, Kool Herc noticed that dancers were responding best to the stripped-back, percussion-heavy drum sections of the funk records he was playing. He began isolating these “breaks,” or “break beats,” and cut between two copies of the same record to create an extended loop, a technique he called the “merry-go-round,” which was inspired in part by the battles he’d seen in Jamaica between dub DJs.

Herc was still a teenager when he first showcased this technique to an unsuspecting audience. On August 11th, 1973, him and his sister, Cindy Campbell, held the “Back To School Jam” in the recreation room at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, a venue that, although lowkey, was a step up from the house parties he’d been playing until then.

“This first hip-hop party would change the world,” Herc later said. He called his crowd, the dancers who adored his breakbeat style, “b-boys” and “b-girls,” the beginnings of the movement that would later be known in hip-hop circles as b-boying, or as the media called it, breakdancing.

By some historical accounts, fellow Bronx DJs Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash were inspired by Herc’s sets, and began to build on his style at their own parties. Bambaataa was the founder of the Universal Zulu Nation, a former street gang that became a hip-hop collective and refuge for disenfranchised young people. (The group eventually disassociated itself from Bambaataa in 2016, following a string of allegations related to child molestation; no charges have been brought against him to date.) Known as the “Master of Records” due to his enormous, enviable record collection and the breadth of the music he played, Bambaataa would go to great lengths to discover the funky breaks hiding in overlooked pieces of music.

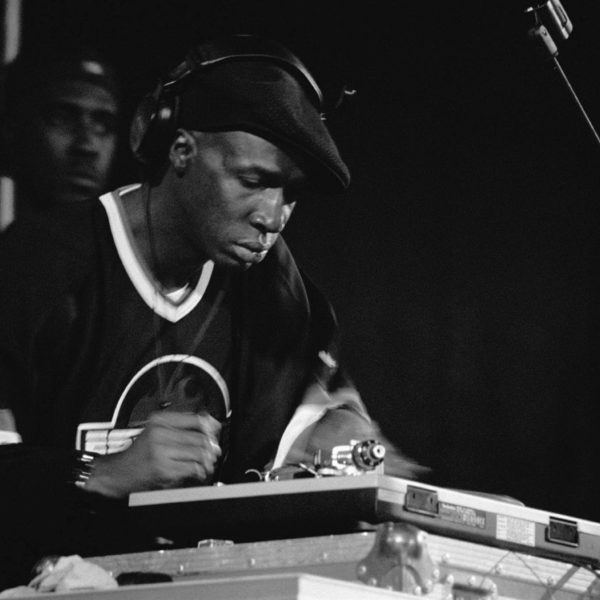

Meanwhile, Grandmaster Flash, who later rose to mainstream prominence with his group Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, was pushing the craft of DJing forward. Where Herc and other DJs cued their records from the faint sound of the needle or by looking at the grooves in the vinyl, Flash built a cue switch for the mixer, enabling him to accurately spin back the record to the beginning of a break in his headphones, something he called the “quick-mix theory” or “backspin technique.”

Then there was “clock theory,” where he marked key sections of the record with tape or crayon, and “punch phrasing,” a technique in which he chopped in short musical phrases using the mixer. It’s now hard to imagine a time in which these techniques weren’t utterly commonplace, something for which we have these early pioneers to thank.