Duncan had experience combining audio with visuals. As a dedicated follower of film, he’d sampled plenty of movie audio and re-soundtracked films with DJ sets. But he could sense a new creative path when he first tried the X1s. “I put my hand on the platter and scratched the video and was like, OK, this is what it’s all been leading towards. This is perfect for me. As soon as I started I was like, this is the tech that I need for creative ideas.”

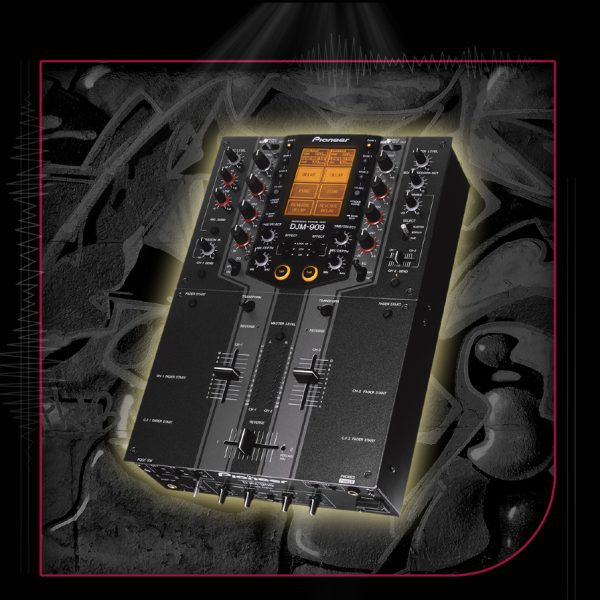

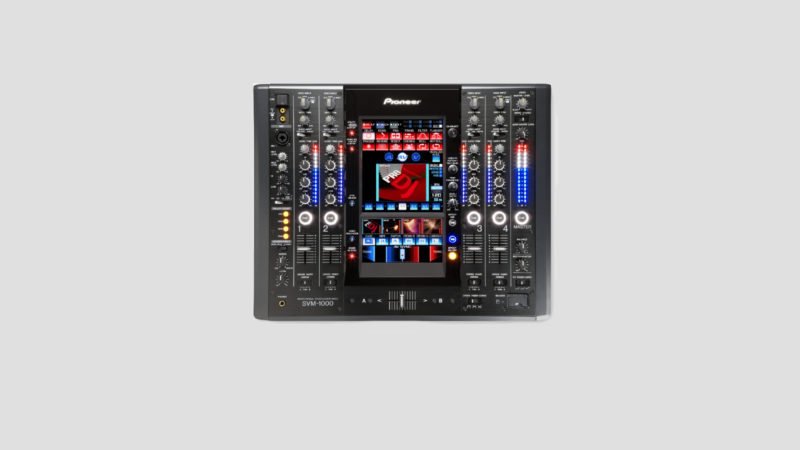

However, the initial excitement over the X1s gave way to technical and logistical challenges. There was no video mixer on the market that functioned in the way DJs like Sander and Duncan needed, so they made do with workarounds. Sander assembled a setup where the video was blended separately by a simple mixer, with the audio handled by a standard DJ mixer. Duncan did something similar, with a regular turntables setup alongside a “big clunky video mixer with just a crossfader to move between the two different video sources.”

“I teamed up with a video artist,” said Sander. “We both figured out a template from which we wanted to work. Let’s say I had 200 records that I wanted to have a choice in playing during any significant night. I would decide that for about 20% of those tunes I would create specific video content for when it had a vocal that we could express on the screen.

“In essence, we wanted to take over the club experience and make it super in-sync with the energy that was coming from the music. The music was always obviously leading, and we wanted to enhance that with visual experiences. So drops would be dark, or breakdowns would be dark and mysterious. We figured out lots of themes and loads of directions that we wanted to use to express a certain emotion from a video.”

“I started thinking about buying DVDs in the same way that I’d been thinking about buying records for 15 years,” said Duncan. “It’s like, I’ve got to start digging for DVDs now. At the time I had a tour in China, just when the X1s came out, and I was digging in all these Chinese DVD shops, buying bootleg copies of every movie, and also weird Chinese folk DVDs—just anything that I could find that might be rare. These weren’t the days of YouTube, you’d have to find DVDs of stuff to get the material that you wanted.”

Duncan described working with DVDs in the live environment as “clunky.” He remembered that on some DVDs it wasn’t possible to skip past the adverts or trailers before the film, meaning he’d have to “cue up” the disc and wait for them to finish. “It was actually a really stressful way of doing things,” he said. “It was innovative and fun and breaking new ground but also tricky to set up and you had to work out a lot of problems.”

There would also be a learning curve as both Duncan and Sander figured out the venues and crowds that would be suitable for visual sets. With a style that drew more from movies than visuals, Duncan concluded that clubs weren’t suitable for what he was trying to do. “I figured out pretty early—it’s amazing, but people cannot dance and watch a screen,” he said. “With my show it was always like, ‘Look at the screen, there’s something going on here that you need to see.’ So sometimes I’d do shows in cinemas, where people sit down and eat popcorn and watch me DJ. And that’s way more exciting to me than trying to get someone’s attention in a club at two in the morning.”

Sander recalled having a huge range of different experiences. “At some moments it was incredible,” he said. “I had a record back then called ‘This Is Miami,’ which was 2005, I believe. I did various versions for various cities where I would play. I remember doing SW4, a huge dance music festival smack in the middle of London. I remember playing the “This Is London” version… and I mean, the crowd just exploded. But in an underground club in, say, New York with ravers who really wanted to get totally locked into the music—this maybe wasn’t the best idea because I was more busy with making sure that everything worked than being fully focused on what actually happened to the dance floor.”